In-class activities with Standing Groups or Teams

In this type of collaborative work, a group or team of students work together over more than one class period, sometimes over an entire semester. The phrase team-based learning sometimes refers to a very specific and structured form of this work. You can learn more about the formal Team-Based Learning technique at the Team-Based Learning Collaborative website. We use the term team-based learning more generally, referring to any in-class group activities where the same teams work together over more than one class session. If you’d like to delve into team-based learning in greater depth, be sure to check out our occasional paper on the topic.

Why use ongoing or standing teams rather than forming groups ad hoc with each activity? There can be several advantages. An ongoing team gets to know each other well, building a sense of community and belonging that can be particularly valuable in large classes. Ongoing teams may be more efficient because students learn how to work with each other. Finally, instructors may design ongoing teams because this design resembles dynamics in the workplace.

-

In-class group activities should include work that is best done as part of a collaboration. Design activities around questions or exercises that are complex or open-ended. A complex problem may have one answer, but it is difficult to reach and would benefit from multiple minds on the task. An open-ended question has no single correct answer, could be controversial, and students may have a variety of perspectives or viewpoints on it.

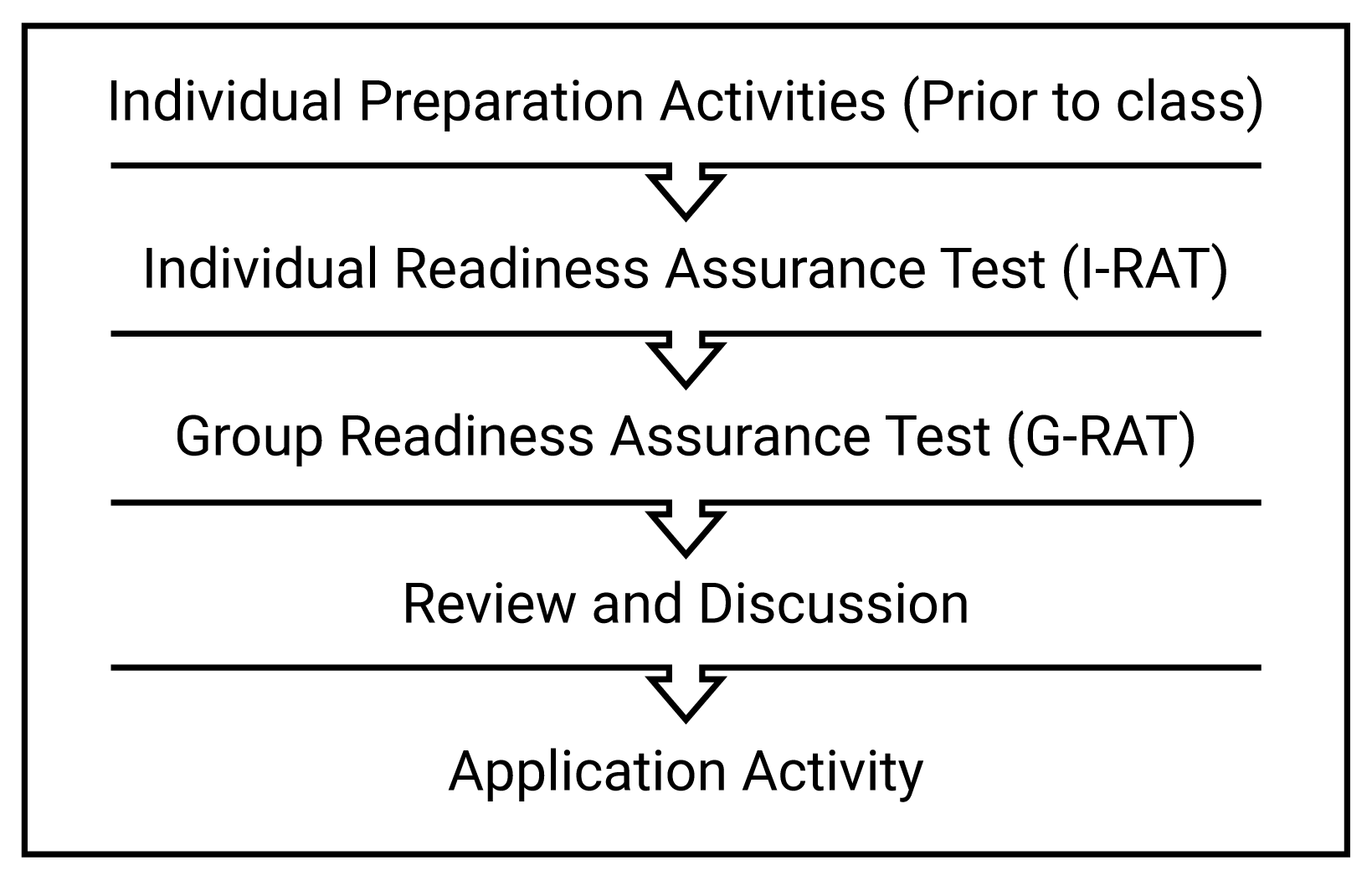

Let’s take a look at formal Team-Based Learning as a model for how an instructor could incorporate standing teams into their course design. This model is more commonly implemented in STEM fields, but applications in the humanities and social sciences are growing (see Sweet & Michaelsen 2012). Prior to working in teams, individual students complete short quizzes to ensure their understanding of material. In formal Team-Based Learning, these quizzes are referred to as Individual Readiness Assurance Tests. These quizzes may take place before class or at the beginning of class. When students turn to work with their teams, the first activity they complete is the same quiz as a group (the Group Readiness Assurance Test). Then they work with their ongoing team actively solving difficult, applied problems, perhaps using a team whiteboard. All teams work on the same problem and report their results simultaneously.

Let’s take a look at formal Team-Based Learning as a model for how an instructor could incorporate standing teams into their course design. This model is more commonly implemented in STEM fields, but applications in the humanities and social sciences are growing (see Sweet & Michaelsen 2012). Prior to working in teams, individual students complete short quizzes to ensure their understanding of material. In formal Team-Based Learning, these quizzes are referred to as Individual Readiness Assurance Tests. These quizzes may take place before class or at the beginning of class. When students turn to work with their teams, the first activity they complete is the same quiz as a group (the Group Readiness Assurance Test). Then they work with their ongoing team actively solving difficult, applied problems, perhaps using a team whiteboard. All teams work on the same problem and report their results simultaneously.Of course instructors need not utilize this particular model. In writing-intensive courses, there are rich opportunities for ongoing peer feedback. In reading intensive courses, ongoing teams can collaboratively annotate course readings using tools such as Perusall. Online courses can build community by assigning small standing groups to their own boards or forums for asynchronous class discussion.

-

We recommend that the instructor create groups. We suggest a few basic principles related to the size, composition, and duration of these groups.

Group Size

We suggest a few basic principles of group formation. Form teams of three to six members. Use smaller teams if you want to prioritize individual accountability and allow for more flexible scheduling when out-of-class activities are required. On the other hand, use larger teams if it's important for teams to bring more resources, ideas, and points of view to the problem.

Heterogeneity

When it comes to long-term, standing teams, we recommend that the instructor create them because the instructor can make them heterogeneous. Heterogeneity is an important characteristic for effective groups and teams. Teams that have a broad range of abilities and problem-solving perspectives among members tend to be more successful than those that are homogeneous in this regard (Brewer & Mendelson, 2003; Heller & Hollabaugh, 1992). Hong and Page (2004) suggest that such functional diversity, or “differences in how people represent problems and how they go about solving them” can be an important attribute of high-performing teams (p. 16385). Similarly, groups that are heterogeneous with respect to students’ social identities can build skills for dialogue across differences, career skills for collaborating in diverse group settings, and introduce students to new perspectives informed by others’ experiences (Finley, 2023; Zúñiga, 2014). Finally, other researchers have also demonstrated that working with peers of different abilities offers benefits to students at all levels—the more capable students become more aware of their thinking processes, while the less capable student learns from an advanced peer (Oakley et al., 2004; Wankat & Oreovicz, 1993).

While diverse groups are valuable for many reasons, one should not assume that just because a group has diverse members that it will work well. For example, some research suggests that when individuals from underrepresented backgrounds are isolated, their team participation can be negatively affected because their opinions may not be considered valid by their teammates, or they may be assigned unimportant tasks (Ingram & Parker, 2002; Michaelsen & Sweet, 2008). Therefore, it is essential to teach teamwork skills to increase the likelihood that all students are able to contribute their ideas and perspectives and no students are excluded or assigned lower-level tasks. Strategies to develop teamwork skills and encourage equitable participation include assigning roles that rotate, developing team contracts, and implementing mechanisms for peer feedback, which can help identify problems with feelings of exclusion. See sections on Group Dynamics and Assessment and Accountability on this site.

You may want to gather data* from students to help you form groups. The University of Michigan’s Center for Academic Innovation supports instructors in the use of Tandem, a web-based tool that automates group formation by leveraging data supplied by students and prioritized by instructors.

*Important legal note: Protected identity characteristics (such as race, ethnicity, sex, etc.) cannot be used to assign students to teams/groups and must not be collected via team formation surveys. If you have any questions, please reach out to the U-M Office of General Counsel.

Group Duration

A final consideration for group formation is how long the standing group will last. In formal Team-Based Learning, teams last the entire semester. Alternatively, you may decide to have standing teams that last for a few classes, a few weeks, or half a semester. The decision comes down to a tradeoff. Rotate groups more regularly if you want students to work with and build relationships with more of their classmates. They will have a wider range of experiences. On the other hand, maintain the same groups over the semester if you want to students to have more time to build social cohesion and learn to address group conflict.

-

The ability of team members to work effectively together can evolve over time as students acquire skills for working together. It is important for students to know that their teams are likely to experience conflict and for instructors to provide students with ways to deal with those conflicts. The suggestions offered in this section highlight good practices for teaching teamwork skills.

Start Strong

A productive group dynamic can start when you are first forming groups. Utilize activities that allow students to get to know each other, reflect on the benefits and challenges of working together, and focus on positive contributions each student brings to the group.

- One activity we recommend is creating a group resume. “The group resume is designed to help students share their skills, talents, knowledge, and experiences with their group members. They are building a resume together to highlight their collective experiences, discuss their contributions, and make visible their value to the group, ” (Barkley et al., 2014). This template might help you as you develop a group resume activity. A variation of this idea is to ask students to complete a skills inventory. You can design the inventory to identify the hard and soft skills you think will be valuable to the group. Students can then rate themselves on each skill. Afterwards, they share their inventories with their teammates and discuss their group’s strengths. The Eberly Center at Carnegie Mellon University created this sample skills inventory as a reference.

- Group reflections on work styles and conflict styles are another low-stakes activity that can promote productive group dynamics right off the bat. With this information, students can preempt conflicts that might arise while working together.

- Ask groups to discuss what makes a group function successfully. Or brainstorm the qualities of a good teammate. Have them use their answers to develop a set of ground rules or norms for their group. Norms can include expectations about how the group will communicate with each other and the process they’ll use to resolve disagreement. This process could lead into the formation of a group contract or charter.

Assign Roles

Individuals can learn about different ways to productively contribute to a group when you assign group members roles. For example, one group member can be the Facilitator, whose role is to moderate discussion and keep the group on task. Another member could be the Devil’s Advocate, whose role is to raise constructive objections and introduce possible counterarguments. These roles can be instructor-determined or established by the groups themselves, e.g., by giving teams a list such as the one below and asking them to decide on and delegate appropriate roles within their group.

The roles you – or your students – assign will depend on the goals of the assignment, the size of the team, etc. They can be fixed or rotating. Some research suggests that underrepresented and minoritized individuals are more likely to be assigned unimportant roles in groups. This is one reason for the instructor to assign roles and rotate them, so that everyone has a chance to develop these skills. Check out this resource for more ideas on possible roles you could assign.

Monitor Dynamics

Teams often need support while individuals learn to interact with a diverse group of their peers. You can monitor group interactions by circulating the room during group activities. Monitoring teams is fundamental to detecting and correcting problematic dynamics in a timely way (Fredrick, 2008). You may find that students need coaching to understand the value of collaboration, to take ownership of and speak confidently about their ideas, to give constructive feedback, and to listen carefully to their classmates. In addition, monitoring teams can help keep them on task. Lastly, when instructors periodically check in with the teams, they are available to answer questions that arise.

Teams often need support while individuals learn to interact with a diverse group of their peers. You can monitor group interactions by circulating the room during group activities. Monitoring teams is fundamental to detecting and correcting problematic dynamics in a timely way (Fredrick, 2008). You may find that students need coaching to understand the value of collaboration, to take ownership of and speak confidently about their ideas, to give constructive feedback, and to listen carefully to their classmates. In addition, monitoring teams can help keep them on task. Lastly, when instructors periodically check in with the teams, they are available to answer questions that arise.Instructors can periodically check-in with the teams, perhaps by scheduling times to meet with each team during office hours or being present when the team works together. During these meetings, the instructor can ask about group decision-making processes and group communication.

One more option for monitoring groups is to ask students to weigh in on group dynamics a few weeks into their collaboration, using a form such as this one from Carnegie Mellon's Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence & Educational Innovation. By reviewing these forms, you can identify groups that aren't functioning well and facilitate conversations and recommend strategies to promote teamwork.

The University of Michigan’s Center for Academic Innovation supports instructors in the use of Tandem, a web-based tool to help monitor group dynamics and teach productive group work skills. By regularly surveying group members, Tandem alerts instructors to groups or teams that may need additional support. Teams that need additional support can be assigned specific lessons on effective group dynamics.

-

A common student complaint about group activities is that individuals in the group contribute unequally without penalty. This concern may be heightened when groups and teams work together in an ongoing relationship because the stakes may be higher than a one-time activity. Here we’ll share some strategies to address this concern, but we also want to point you to the CRLT Occasional Paper No. 35 for more ideas and resources to assess collaborative work.

- Ask students to do individual work before entering their group. Require students to work individually first (i.e., have them complete a worksheet or assignment, answer questions, or make a choice) so that each member has something to contribute to the group. An individual assignment/assessment completed before class could be used as each student’s prerequisite “ticket” into the group activity.

- Provide clear instructions to the groups. Be sure to describe the task you’ve asked groups to perform, communicating milestones so groups can monitor and reflect on their progress and performance. Verbalize how much time groups have to complete the task. Include the product or deliverable you’ll ask for at the end of the task. For example, you may ask them to hand-in a worksheet or present their solution to the class.

- Encourage individual accountability through a grading system. If you decide to grade group work, a grading system should include (1) individual performance/products; (2) group performance/products; and (3) each member’s contribution to team success (e.g., peer evaluation). Be sure to plan in advance how you will evaluate each of these three aspects and how you will communicate your expectations and/or grading criteria to students. Here is a resource to help you develop a grading scheme for group work.

Use peer evaluations

Because students have the most knowledge about individual contributions to the team, peer evaluations are an important ingredient in an instructor’s team assessment (Cestone et al., 2008; Loughry et al., 2007; Williams et al. 2002). When effectively facilitated, the benefits of peer evaluation are many. Soliciting students’ perspectives of their peers can help an instructor identify “free riders” who fail to contribute to the team and rely on others to get the work done (Glenn, 2009; Slavin, 1995). Students are challenged to think more critically about the process of teamwork (Fredrick, 2008), they reflect on the goals and objectives of a course (Cestone et al., 2008), and they are more motivated to produce high-quality work when their peers evaluate them than when their instructor does (Searby & Ewers, 1997). Research also shows that students who participate in peer evaluation have an increased awareness of the quality of their own work and increased confidence in their abilities (Dochy et al. 1999). On the whole, students find peer evaluation to be a fair method of assessment (Gatfield, 1999) and are generally very satisfied with the process (Cestone et al., 2008).

Peer evaluation can also be useful to improve team interactions while the teamwork is in progress. To accomplish the first objective, instructors should distribute peer evaluations at multiple points during the term so students can learn how to score their teammates and get used to sharing their (anonymous) ratings with teammates. And at the end of the term, the instructor can factor the students’ ratings into the overall grade or adjust each student’s team score by a multiplier based on the ratings to reflect their team contributions (Kaufman et al., 2000). Though it is important to make peer ratings count, if the course becomes overly dependent on them, students may start to feel as if they have not received appropriate credit for their individual efforts, and the peer feedback may become counterproductive.

Consider whether you will ask students to self-assess their own participation in the group when they complete peer evaluations. Self-assessment provides students with an opportunity to practice reflection and self-monitoring, encourages academic integrity, and helps students develop as independent learners. Adding self-assessment, however, is not without challenges. For example, lower performing and less experienced students may overestimate their contributions. Students may need guidance and time to become more accurate with their assessment.

Web-based tools exist to support peer evaluation.

Tandem: The University of Michigan’s Center for Academic Innovation supports instructors in the use of Tandem, a web-based tool to help monitor group dynamics and teach productive group work skills. One feature of the tool is a mid-term and end-of-term peer and self-assessment. Visit the Tandem website to learn more.

University centers for teaching and learning have created some helpful resources to support faculty using peer assessment of group working including:

- Using Peer Assessment to Make Teamwork Work: A Resource Document for Instructors by Teaching and Learning Services at McGill University.

- Peer Assessment of Group Work by the Center for Teaching and Learning at Columbia University.

- Sample Peer Assessment Form #1 by the Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence & Educational Innovation at Carnegie Mellon University.

- Sample Peer Assessment Form #2 by the Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence & Educational Innovation at Carnegie Mellon University.

-

Barkley, E., Cross, P., & Major, C. (2014). Collaborative learning techniques. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Brewer, W., & Mendelson, M. I. (2003). Methodology and metrics for assessing team effectiveness. International Journal of Engineering Education, 19(6), 777-787.

Cestone, C. M., Levine, R. E., & Lane, D. R. (2008, Winter). Peer assessment and evaluation of team-based learning. In L. K. Michaelsen, M. Sweet, & D. X. Parmelee (Eds.), Team-based learning: Small group learning’s next big step (pp. 69-78). New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 116. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Fredrick, T. A. (2008). Facilitating better teamwork: Analyzing the challenges and strategies of classroom-based collaboration. Business Communication Quarterly, 71(4), 439-455.

Finley, A. P. (2023). The career-ready graduate: What employers say about the difference college makes. American Association of Colleges and Universities.

Gatfield, T. (1999). Examining student satisfaction with group projects and peer assessment. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 24(4), 365-377.

Glenn, D. (2009, June 8). Students give group assignments a failing grade. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Heller, P., & Hollabaugh, M. (1992). Teaching problem solving through cooperative grouping. Part 2: Designing problems and structuring groups. American Journal of Physics, 60(7), 637-644.

Hong, L., & Page, S. E. (2004). Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(46), 16385-16389.

Ingram, S., & Parker, A. (2002). Gender and modes of collaboration in an engineering classroom: A profile of two women on student teams. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 16(1), 33-68.

Kaufman, D. B., Felder, R. M., & Fuller, H. (2000). Accounting for individual effort in cooperative learning teams. Journal of Engineering Education, 89(2), 133-140.

Loughry, M. L., Ohland, M. W., & Moore, D. D. (2007). Development of a theory-based assessment of team member effectiveness. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 67(3), 505-524.

Michaelsen, L. K., & Sweet, M. (2008). The essential elements of team-based learning. In L. K. Michaelsen, M. Sweet, & D. X. Parmelee (Eds.), Team-based learning: Small group learning’s next big step (pp. 7-27). New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 116. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Oakley, B., Felder, R. M., Brent, R., & Elhajj, I. (2004). Turning student groups into effective teams. Journal of Student Centered Learning, 2(1), 9-34.

Searby, M., & Ewers, T. (1997). An evaluation of the use of peer assessment in higher education: A case study in the School of Music, Kingston University. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 22(4), 371-383.

Slavin, R. E. (1995). Cooperative learning (2nd ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Sweet M., & Michaelsen, L. K. (2012). Team-based learning in the social sciences and humanities: Group work that works to generate critical thinking and engagement. Sterling, Va. : Stylus Publishing.

Tonso, K. L. (2006). Teams that work: Campus culture, engineering identity, and social interactions. Journal of Engineering Education, 95(1), 25-37.

Wankat, P. C., & Oreovicz, F. S. (1993). Teaching engineering. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Williams, D., Foster, D., Green, B., Lakey, P., Lakey, R., Mills, F., & Williams, C. (2002). Effective peer evaluation in learning teams. In C. Wehlburg & S. Chadwick-Blossey (Eds.), To Improve the Academy: Resources for Faculty, Instructional, and Organizational Development, Vol. 22 (pp. 251-267). Bolton, MA: Anker.

Zúñiga, X., Lopez, G. E., & Ford, K. A. (2014). Intergroup dialogue: Critical conversations about difference. In X. Zúñiga, G. E. Lopez, & K. A. Ford (Eds.), Intergroup dialogue: Engaging difference, social identities and social justice. Routledge.