The easiest entry-point for incorporating group work into a course is through informal, in-class group activities. You can utilize these activities in any class size and across disciplines. In this type of collaborative work, groups are often formed ad hoc, and they work together on a single question or problem. To make these activities effective, instructors will want to pay particular attention to the design of the activity, the process of group formation, and accountability mechanisms.

-

Group activities should include work that is best done as part of a collaboration. Design activities around a question or exercise that is complex or open-ended. A complex problem may have one answer, but it is difficult to reach and would benefit from multiple minds on the task. An open-ended question has no single correct answer, could be controversial, and students may have a variety of perspectives or viewpoints on it. See fig. 1 for some examples of open-ended or complex tasks.

Fig. 1 Open-Ended and Complex Tasks

- Interpret a graph or chart

- Make a prediction from a demonstration

- Brainstorm to elicit prior knowledge of a topic

- Develop a recommendation

- Correct the error

- Analyze a text or piece of media

- Evaluate a statement

There are a number of ways to design your group activity. In STEM courses, you might ask groups to collaborate on problem-solving or compare answers to a problem. This opens the door to informal peer instruction. Other complex activities include interpreting a graph and making a prediction from a demonstration. In writing-intensive courses, there are rich opportunities for peer feedback. Ask a pair of students to share a short portion of their writing, such as the literature review or the introduction, with their partner in-class.

Open-ended questions can be formatted as a think-pair-share activity. You would ask individuals to collect their own thoughts on the question. Then they would compare and synthesize their individual responses with a classmate to be shared with the larger class. Think-pair-share activities are valuable for a couple of reasons: first, they give students an opportunity to develop their own thoughts on a question. In addition, they allow students to feel more comfortable sharing their thoughts, having tested them out on a classmate first. Not to mention that pairs can learn from their partners and improve on their answers.

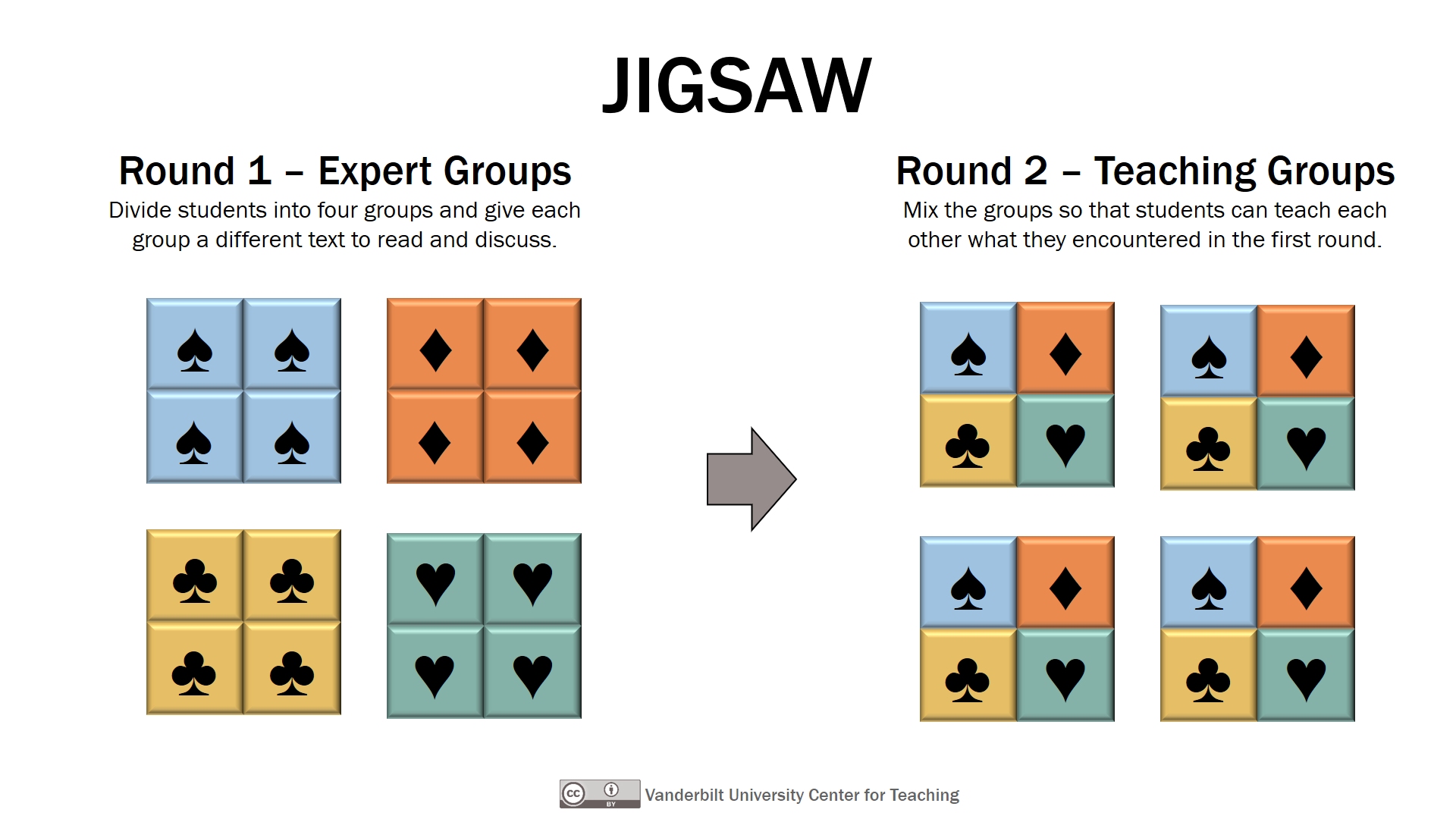

Another type of in-class group work is a jigsaw discussion. In this technique, a general topic is divided into smaller, interrelated pieces (similar to the way a puzzle is divided into pieces). The first step of a jigsaw activity involves creating groups of 3-5 people. In each of these groups, the members together become experts on a topic. For example, each group could be assigned a different article or case study. After the original groups become experts on their topic–their piece of the puzzle–they are reassigned to new groups. One expert from each topic area joins each new group. The experts teach the other group members about that puzzle piece. Finally, after each person has finished teaching, the puzzle has been reassembled, and everyone on the team knows something important about every piece of the puzzle. The figure above, created by Vanderbilt University's Center for Teaching, may help you visualize the stages of a jigsaw discussion. Jigsaw activities can be effective because they have both a mechanism for individual accountability and promote positive interdependence.

We’ve discussed a handful of designs for ad hoc group activities. Check out this resource for more ideas.

-

Group Size

How many students do you assign to each group? When deciding on the size of your student groups keep a couple factors in mind. First, smaller groups better facilitate individual accountability (Aggarwal and O’Brien, 2008). Every member is more likely to participate. On the other hand, larger teams have the potential for more resources, ideas, and points of view to be brought to the problem. In general, we recommend teams of three to six students (Birmingham & McCord, 2004; Johnson, Johnson, & Smith, 1998).

Another advantage of larger groups is that they can help avoid isolating individuals from minoritized or underrepresented groups. Some research suggests that when individuals from underrepresented backgrounds are isolated, their team participation can be negatively affected because their opinions may not be considered valid by their teammates, or they may be assigned unimportant tasks (Ingram & Parker, 2002; Michaelsen & Sweet, 2008). For this reason, you may also consider assigning students roles in their groups and rotating those roles.

Assigning Groups

We encourage you to assign students to groups even in large classes or under time constraints. When instructors create groups, it usually allows for more group heterogeneity, which is an important characteristic for effective groups. Groups that have a broad range of abilities and problem-solving perspectives among members tend to be more successful than those that are homogeneous in this regard (Brewer & Mendelson, 2003; Heller & Hollabaugh, 1992). Hong and Page (2004) suggest that such functional diversity, or “differences in how people represent problems and how they go about solving them” can be an important attribute of high-performing teams (p. 16385). Other researchers have also demonstrated that working with peers of different abilities offers benefits to students at all levels—the more capable students become more aware of their thinking processes, while the less capable student learns from an advanced peer (Oakley et al., 2004; Wankat & Oreovicz, 1993).

How can you quickly assign students to pairs or groups? One option is to assign groups randomly using one of the following approaches:

- Counting off by the number of groups

- Asking students to pick up a number or colored card as they enter the class.

Alternatively, you could assign groups based on some criterion. For example, you could assign students to groups based on:

- who read what article

- common interests

- birth month

In large classes, your GSI team may play a valuable role in the group-formation process. You can divide the classroom into sections and have a GSI assign groups in each section. They can clarify instructions about how to form groups. GSIs can also identify and guide students who are hesitant about which group to join.

-

A common student complaint about group activities is that individuals in the group contribute unequally without penalty. Here are some strategies to address this concern.

- Ask students to do individual work before entering their group. Require students to work individually first (i.e., have them complete a worksheet or assignment, answer questions, or make a choice) so that each member has something to contribute to the group. An individual assignment/assessment completed before class could be used as each student’s prerequisite “ticket” into the group activity.

- Provide clear instructions to the groups. Be sure to describe the task you’ve asked groups to perform, communicating milestones so groups can monitor and reflect on their progress and performance. Verbalize how much time groups have to complete the task. Include the product or deliverable you’ll ask for at the end of the task. For example, you may ask them to hand-in a worksheet or present their solution to the class.

- Designate roles in the group. For example, one group member can be the Facilitator, whose role is to moderate discussion and keep the group on task. Another member could be the Devil’s Advocate, whose role is to raise constructive objections and introduce possible counterarguments. These roles can be instructor-determined or established by the groups themselves, e.g., by giving teams a list of potential roles and asking them to decide on and delegate appropriate roles within their group.

- Establish reporting back or debriefing methods that encourage accountability. Remember it is best to establish and explain the procedure at the beginning of the activity to set the tone and expectations for group work. If you have established a safe learning environment, one way to ensure accountability is to call randomly on students to present their group’s progress or final product.

-

After students complete a group activity, you may ask them to report out or debrief their work. Reporting out is valuable because, when a group reports out, they share the product of their time together so that groups can learn from each other. When they debrief, they think and reflect on the groups’ output and process. Reflection is important to learning because it gives students time to draw meaning and insights from their experiences.

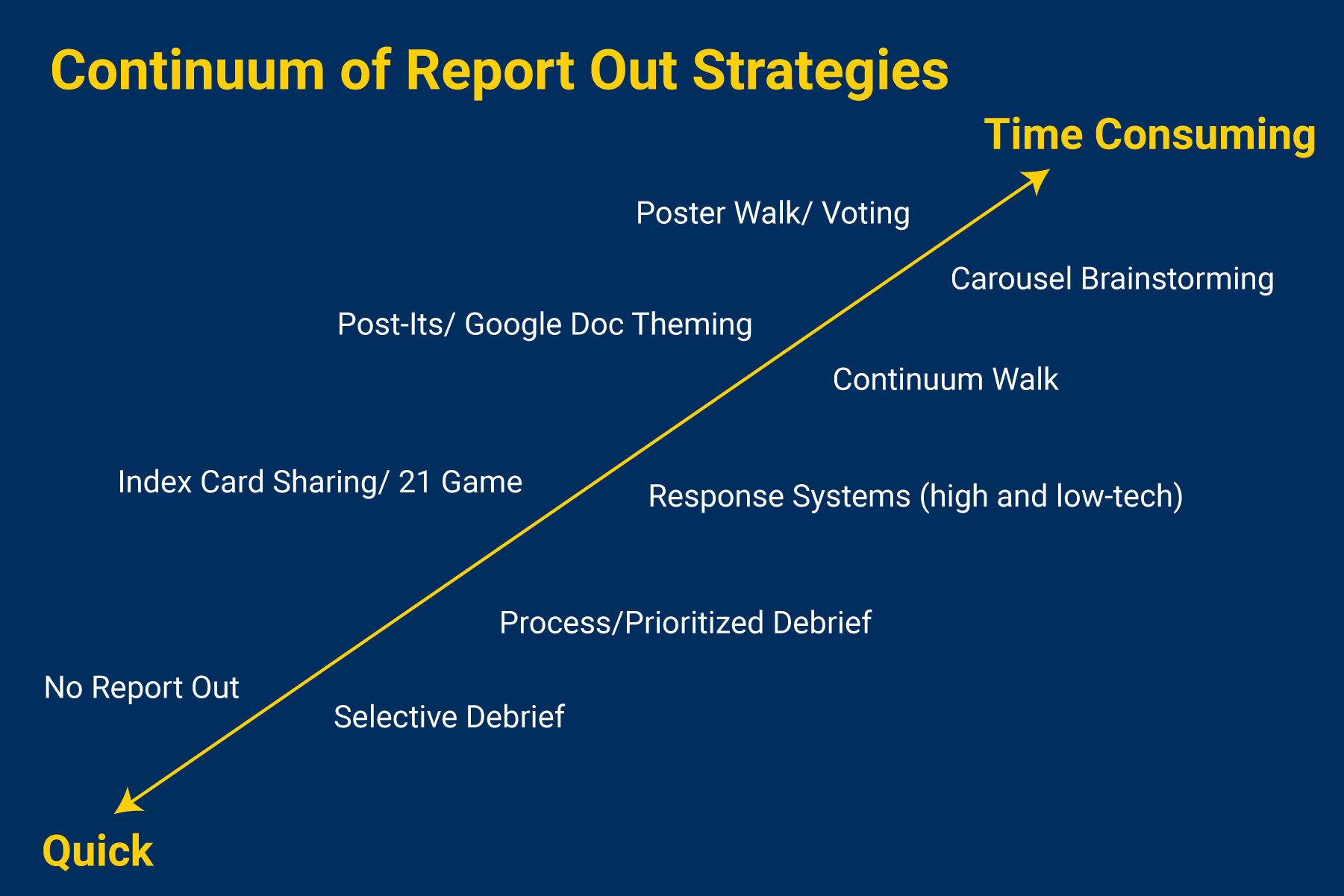

Select a reporting out mechanism that promotes high-energy class discussions and reflections. Minimize the lecture mode of group sharing (i.e., a series of group presentations). Try not to ask groups to summarize everything they did or discussed during the activity. Instead keep the groups’ output for class discussion simple and focused. While it’s common to ask each group to share briefly aloud, there are a range of reporting out options that vary in complexity and time commitment. Here are a few:

No Report Out: Not all small-group discussions have to be reported out. Be selective about which ones need to have full-group processing.

Selective Report Out: Encourage groups to listen to their colleagues by asking them to only share ideas that haven’t already been mentioned or by asking them to compare their response to previous groups’ comments.

Index Card Sharing: Participants write one key take-away from the discussion on an index card. These can be read quickly by the instructor to identify key themes or questions to discuss as a large group. If the ideas can/should be shared, the cards can be passed back out to students for individuals to read and respond to another individual’s comment.

Theming via Post-Its or Collaborative Documents: Groups submit one or two key ideas from their discussion in a venue that all students have access to. This could be done online with Google Docs or Google Slides. Alternatively, they could write on post-it notes and put them on a white board. This has a built-in debriefing activity where ideas are sorted into categories by participants and instructors as they are placed.

Response systems: Polling or other classroom response systems could be used to vote on group submissions. For example, if groups are asked to generate an analogy that illustrates a course concept -- all submissions could be compiled as a candidate for "best analogy." This process can be low-tech too! Ask for a show of hands to get input.

After reporting out, consider asking your students to debrief. Debriefing is an opportunity for students to digest, process, compare and contrast, and evaluate the output of other groups. What are some ways to debrief the activity? You might ask groups to share what was challenging for their group or what strategies enabled their group.

You can debrief group activities with individual reflections as well. Here are a few questions you might pose with this approach to debriefing:

- Did something come up in your group that you haven’t thought about before—or that pushed you to think in a new way?

- What’s one thing you learned from one of your classmates in your group today?

- What remains unresolved?

- What perspectives are missing from this discussion so far?

- Based on our discussions today, what will you be thinking about after you leave?

-

Aggarwal, P., & O’Brien, C. L. (2008). Social Loafing on Group Projects: Structural Antecedents and Effect on Student Satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Education, 30(3), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475308322283

Birmingham, C., & McCord, M. (2004). Group process research: Implications for using learning groups. In L. K. Michaelsen, A. B. Knight & L. D. Fink (Eds.), Team-based learning: A transformative use of small groups in college teaching (pp. 73-93). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Brewer, W., & Mendelson, M. I. (2003). Methodology and metrics for assessing team effectiveness. International Journal of Engineering Education, 19(6), 777-787.

Heller, P., & Hollabaugh, M. (1992). Teaching problem solving through cooperative grouping. Part 2: Designing problems and structuring groups. American Journal of Physics, 60(7), 637-644.

Hong, L., & Page, S. E. (2004). Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(46), 16385-16389.

Ingram, S., & Parker, A. (2002). Gender and modes of collaboration in an engineering classroom: A profile of two women on student teams. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 16(1), 33-68.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (1998). Maximizing instruction through cooperative learning. ASEE Prism, 8(2), 24-29.

Michaelsen, L. K., & Sweet, M. (2008). The essential elements of team-based learning. In L. K. Michaelsen, M. Sweet, & D. X. Parmelee (Eds.), Team-based learning: Small group learning’s next big step (pp. 7-27). New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 116. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Oakley, B., Felder, R. M., Brent, R., & Elhajj, I. (2004). Turning student groups into effective teams. Journal of Student Centered Learning, 2(1), 9-34.

Wankat, P. C., & Oreovicz, F. S. (1993). Teaching engineering. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.