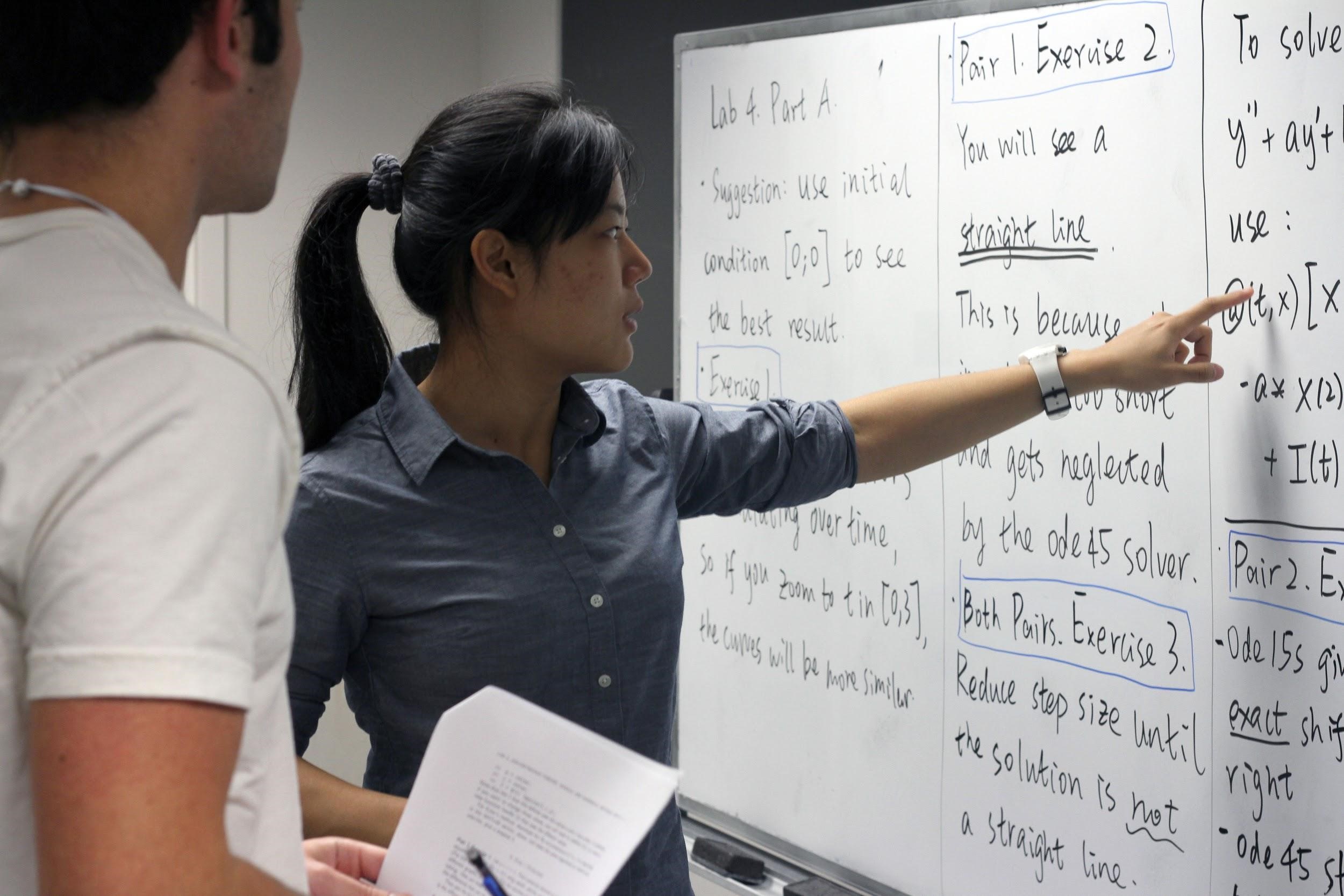

With the construction of dedicated active learning spaces across U-M’s campus, widespread professional development focused on active learning, and many instructors looking to increase student engagement, students are experiencing active learning more and more in their time at the University of Michigan. But how do students perceive this kind of instructional approach? Studies have indicated that the majority of students respond positively to active learning, and although resistance occurs, it occurs at relatively low levels (Finelli et al, 2018). However, a new study points to a potential aspect of students' experiences of learning in such classrooms that instructors may want to address (Deslauriers et al, 2019). In short, while students in active learning classrooms learn more, they may feel that they have learned less.

With the construction of dedicated active learning spaces across U-M’s campus, widespread professional development focused on active learning, and many instructors looking to increase student engagement, students are experiencing active learning more and more in their time at the University of Michigan. But how do students perceive this kind of instructional approach? Studies have indicated that the majority of students respond positively to active learning, and although resistance occurs, it occurs at relatively low levels (Finelli et al, 2018). However, a new study points to a potential aspect of students' experiences of learning in such classrooms that instructors may want to address (Deslauriers et al, 2019). In short, while students in active learning classrooms learn more, they may feel that they have learned less.

The authors looked at students’ outcomes and their perceptions of learning in a large-enrollment introductory physics course (Deslauriers et al, 2019). While this study was performed in a STEM classroom, the researchers highlight ways in which these principles might also be extended into non-STEM active learning classrooms. Students in the course were divided into two random groups: one which would experience “active instruction (following best practices in the discipline)” while the second group received “passive instruction (lectures by experienced and highly rated instructors).” These groups then switched the type of learning they did in a subsequent unit, to allow for comparison. Students participating in the active learning sections earned higher grades, suggesting they learned more. But in self-reported surveys, those students perceived that they had learned less compared to the lecture-based sections.

As we pass the middle of the term, instructors are asked to think about course evaluations that students complete at the end of the term (November 19-December 9). By November 17, U-M instructors are invited to preview evaluation questions and create a few of their own if they wish. What principles or goals might guide you in that process?

As we pass the middle of the term, instructors are asked to think about course evaluations that students complete at the end of the term (November 19-December 9). By November 17, U-M instructors are invited to preview evaluation questions and create a few of their own if they wish. What principles or goals might guide you in that process? With the construction of dedicated

With the construction of dedicated  Faculty and GSIs from across campus are invited to explore

Faculty and GSIs from across campus are invited to explore