What does ‘transparency’ mean in a teaching-learning context, and why is it a key principle featured in many CRLT workshops and resources about inclusive teaching? At its simplest, transparency means clearly communicating with students about course expectations and norms. As outlined below, such transparency can lead to more equitable learning experiences. That’s why transparency is the focus for this year’s Inclusive Teaching @ Michigan May workshop series. (Registration available here; for more details about both transparency and the May series, read on.)

A key scholar of transparency in teaching and learning, Mary-Ann Winkelmes further defines transparency as a process in which teachers and students are engaged in “focusing together on how college students learn what they learn and why teachers structure learning experiences in particular ways.” Winkelmes and her collaborators have developed a model that more precisely defines transparency as clarity about the purpose, task, and criteria of learning activities and assignments. To unpack those terms:

- Purpose: What is the activity designed to help students learn, practice, or develop? Why is this the way the learning is structured?

- Task: What exactly are students to do? What are the parameters of the activity?

- Criteria: How will student learning be assessed? What do relative levels of success with the task look like?

Recent studies have shown that clear communication about these factors benefits all students’ learning but is especially beneficial to the learning of first-generation students and others who have been historically underserved by higher education, including students of color. In short, transparency can minimize important barriers to equity in learning.

Why might this be? It may seem that, simply by virtue of being enrolled in the same course together (where they are given the same syllabus, assignments, office hours schedule, information about resources such as tutoring, etc.), all students have equal access to the same information and resources to support their learning. But an inclusive teaching framework -- one that focuses on ways systemic inequities can influence students’ access to and experience of education -- calls attention to differences that can result in disparities in learning if instructors are not deliberately transparent about their expectations. Consider:

- Higher ed is often described as operating with a ‘hidden curriculum,’ which assumes students know or can readily find out from family or friends information such as: what office hours are and how professors might expect students to use them, what productive discussion participation looks like, or how to access the most beneficial study supports. The answers to these questions are, of course, not consistent across learning contexts, but explicit communication about how they differ can be rare. Students who come to college connected to social networks where lots of friends and family have higher ed experience often benefit from informal information-sharing not readily accessible to those with fewer ties to higher ed (or whose ties are outside the U.S., in educational contexts where very different norms or expectations prevail).

- Students can be more or less likely to ask questions or avail themselves of learning supports based on their backgrounds and social identities. If, for instance, a student is one of only a few in a class who visibly hold a particular identity (e.g., their race, gender identity, or disability status), they might reasonably be cautious about asking questions that could make them look ignorant or less competent in the eyes of classmates who might unfairly view them as a ‘representative’ of their identity group. Or if a student was previously educated in a cultural context where the student-instructor relationship is relatively formal and hierarchical (which is the case for many of our international students), the student might understandably regard asking questions that haven’t been invited as a sign of disrespect for the instructor. Or if a student comes from a social background where self-sufficiency is regarded as a key virtue, they may be more likely to struggle independently than seek help when they are trying to master challenging material.

The negative learning consequences that sometimes result from such differences can be mitigated by deliberate instructional practices that proactively inform students about: 1. the intentions behind course and assignment design, 2. the precise expectations of student performance (including the best ways to get questions answered), and 3. the ways student learning will be assessed. Such information can also make a big difference in terms of students’ experience of a sense of belonging in the learning environment, counteracting feelings of isolation or marginalization that can occur when a learner believes (accurately or not) that they know or understand less than their peers.

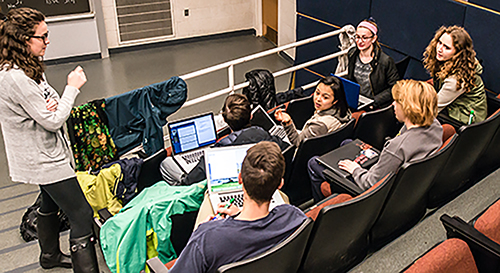

To give instructors opportunities to learn more about these topics and think with others about best practices, CRLT will be organizing this year’s popular May teaching workshop series for U-M instructors, Inclusive Teaching @ Michigan, around the theme of transparency. This is the fourth consecutive year of this series, which offers a range of workshops, open to all U-M instructors, on topics related to equity and inclusion in teaching and learning spaces. Instructors are welcome to attend one or all of the workshops in the one-week series, which will feature sessions that connect in a range of ways to the theme of transparency. The full slate of offerings includes:

- Transparency for Equity: Principles of Transparent Assignment Design

- Understanding How Stereotype Threat, Impostor Syndrome, and Growth Mindset Affect Student Learning

- Disability and Accessible Teaching: Current Perspectives and Best Practices

- Managing Emergent Crises in Diverse Student Teams

- Applying Principles of Transparency to Classroom Discussions

- Inclusive Teaching Means Inclusive Grading Practices Too

- Teaching About Race & Ethnicity in Predominantly White Classrooms

- Teaching in Tumultuous Times: Making Choices about How to Address the World Beyond Your Classroom

As always, if you want to meet individually with a CRLT consultant to discuss ways to increase the transparency of your teaching materials and practices, you can request an appointment online or by calling.

Winkelmes, Mary-Ann. 2013. “Transparency in Teaching: Faculty Share Data and Improve Students’ Learning.” Liberal Education 99 (2): 48-55.

- Log in to post comments

- 677 views