How and why might you work with community partners to enhance student learning in your courses and build valuable connections beyond the university -- whatever your discipline? In this guest post, our partners from the Ginsberg Center offer key insights for planning courses that build productive, equitable relationships with community partners, including guidance for engaging during COVID-19.

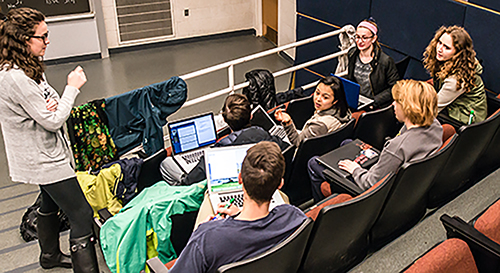

Community-engaged learning, also referred to as service-learning or community-based learning, has been recognized as a high impact educational practice that promotes deeper understanding of course concepts while advancing connections between the university and communities (Kuh, 2008). Community partners bring valuable knowledge and expertise to contribute to students’ learning, and partnering with the university, through community-engaged courses, research and student organizations, can expand community partners’ capacities to address their priorities.

Integrating community-engaged pedagogies into your courses allows students to learn by engaging with communities and social issues, while preparing students for a lifelong commitment to civic engagement. Community-engaged courses are transformative because they help students build highly transferable skills. Since students are increasingly seeking out such opportunities, offering more community-engaged courses can serve as a strategy to attract students to a major or discipline.

While the current circumstances have necessitated shifts to online formats, many have noted the practical benefits of conducting community-engaged courses online (Strait & Nordyke, 2015), and studies have indicated that the positive learning outcomes associated with community engaged-learning (CEL) can also accrue from online CEL (McGorry, 2012; Waldner, McGorry, & Widener, 2012).

But how do you make these learning experiences, especially online, both transformative for students and equitable for our community partners? Below we highlight specific strategies, pulled from our Best Practices for Community-Engaged Learning & Teaching.

Working with Community Partners

- To identify potential community partners

- Discover new potential partners by reviewing existing databases of volunteer opportunities or reaching out to the Ginsberg Center, which works with community partners in the social sector to identify community-defined priorities for addressing pressing social challenges.

- Reach out to colleagues to see if they have existing relationships with community partners who may have additional needs or priorities that you can support.

- To establish effective campus-community partnerships

- Before solidifying your course design, work with community partners to align their interests and priorities with your goals, expectations for student learning, partnership-related outcomes, and course timeline.

- Ask community partners to share additional history and context about the issues they are addressing and who else in the community is working on the issues.

- Have honest and direct conversations about both the parameters and the limitations of the partnership. Be conscious of not promising more than you can deliver.

- Lay out your expectations for your partnership in writing (shared goals, expectations, concrete deliverables, communication and conflict resolution plans, and how to conclude the partnership). You can create a joint Summary of expectations or project charter.

Designing Your Course

- To ensure purposeful design

- What do you (and your community partner) want your students to have learned or accomplished by the end of the term? Let this vision guide your course design.

- Give students structured time to reflect on their thoughts and experiences prior to engaging with communities and address their collective assumptions and expectations.

- Integrate the community-engaged experience into the course by dedicating time to necessary training around skills such as cultural humility, building rapport, and project management strategies.

- Count the time at community sites as part of the “preparation time for class” and balance reading and homework assignment accordingly.

- Request a consultation with Ginsberg Center staff to get support and resources for your course development.

- To integrate substantive reflection

- Provide strategically timed opportunities for your students to reflect on their experiences throughout the term.

- Promote inclusive teaching by using varied platforms for reflection like journaling, class discussion and/or discussion boards, (digital) storytelling, or different types of artistic expression

- Design a mutually beneficial “culminating project,” with community partner input, that will give students an opportunity to showcase and reflect on what they have learned, while providing community partners with tangible outcomes that benefit them.

- Make time to reflect on your own teaching, including how technology has affected both your teaching and community engagement, and talk with your partners and students about what could be changed or enhanced.

- To adapt to the virtual environment

- With your community partner, use your learning objectives to determine what technology tools are most appropriate and the appropriate blend of synchronous and asynchronous instruction, given variations in schedules and access to technology.

- Give community partners access to all virtual components of the course, including discussion boards, course announcements, and readings.

- Consider how power imbalances might manifest in specific forms of virtual interactions (video meetings, phone meetings, email, discussion boards, etc.) and establish a plan for how issues will be identified and counteracted.

- Use technology to allow students to reflect in multiple ways: online journals, group discussion boards, videos, and audio recording.

- We offer additional suggestions and resources in our Best Practices for Online Teaching and on our website.

For additional support with your community-engaged course, contact the Ginsberg Center.

References and Additional Reading

Ash, S. L., & Clayton, P. H. (2009). Learning through Critical Reflection: A Tutorial for Service-Learning Students (Instructor Version). Raleigh, N.C.: Ash, Clayton & Moses.

Fitzgerald, H. E., Bruns, K., Sonka, S. T., & Furco, A. (2012). The Centrality of Engagement in Higher Education. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 16(3), 7–27.

Howe, C. W., Coleman, K., Hamshaw, K., & Westdijk, K. (2014). Student Development and Service-Learning: A Three-Phased Model for Course Design. The International Journal of Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement, 2(1), 44-62.

Jacoby, B. (2014). Service-learning essentials questions, answers, and lessons learned. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter. Association of American Colleges & Universities. (High-Impact Educational Practices: A Brief Overview)

McGorry, S. (2015). HYBRID IV: EXTREME eSERVICE-LEARNING: Online Service-Learning in an Online Business Course. In J. R. Strait & K. Nordyke (Eds.), EService-learning: Creating experiential learning and civic engagement through online and hybrid courses (pp. 119-129). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Mitchell, T. D. (2008). Traditional vs. critical service-learning: engaging the literature to differentiate two models. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 14(2), 50-65.

Strait, J., & Nordyke, K. (2015). Eservice-learning: Creating Experiential Learning and Civic Engagement through Online and Hybrid Courses. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Waldner, L. S., McGorry, S. Y., & Widener, M. C. (2012). E-service-learning: The evolution of service-learning to engage a growing online student population. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 16(2), 123–150.

- Log in to post comments

- 66 views